An aging population, increasing rates of chronic diseases, and rising healthcare costs represent important pressures towards forms of self-management of health and disease outside health care institutions. New techniques of self-management have become feasible owing to the advent of a variety of personal e-health systems, including wearable sensors (Swan, 2012), personal health records (Johansen and Henriksen, 2014) and self-management and empowerment applications for a number of diseases (Samoocha et al, 2010), delivered via smart phones or other portable personal devices (Mosa et al, 2012), as well as via integrated smart home environments (Teng et al, 2008; Pantelopoulos and Bourbakis, 2010).

Personal e-health systems are designed to be used by the citizens themselves to acquire, store, and manage personal health data. This single user access makes it easy to forget or ignore the inherent security and privacy risks involved. Privacy-related legislation, e.g. the European Data Protection Directive (European Parliament, 24 Oct. 1995) and the HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) (104th U.S. Congress, 21 Aug. 1996) explicitly define the rules for protecting the privacy of patients and covers issues, such as access rights to data, how and when data are stored, security of data transfer, data analysis rights, and governance policies. However, it is widely recognized that taking a strong regulatory approach is not always enough, and that privacy safeguards should be built in the design, operation and management of information processing technologies and systems (European Commission, 2012).

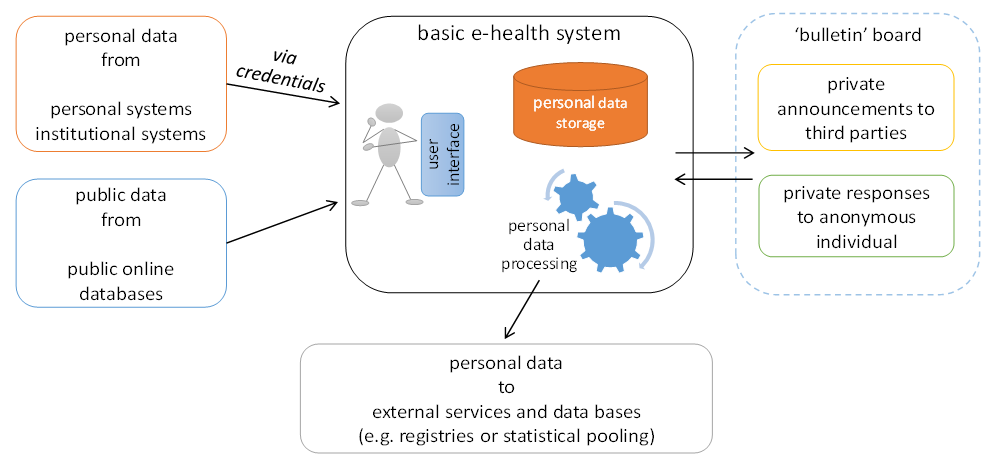

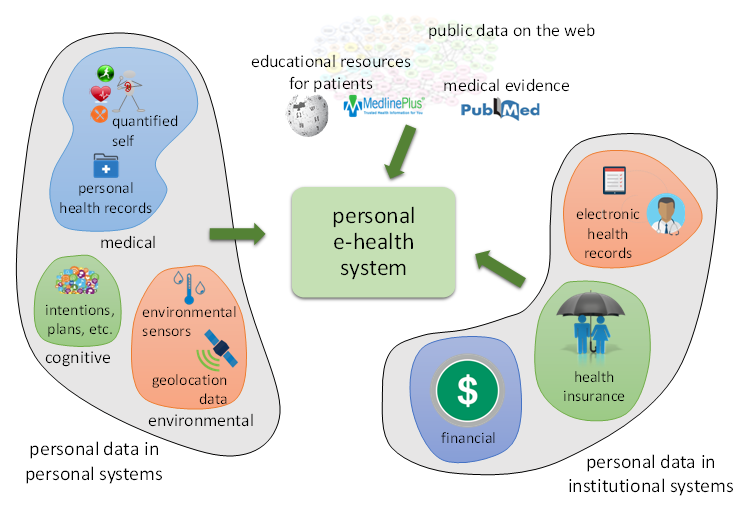

Figure 1: Data communication requirements in a personal e-health system.

Figure 1: Data communication requirements in a personal e-health system.

Based on the requirements for personal data communication in a personal e-Health system (Figure 1), the following five basic personal e-health systems functionalities can be identified:

- personal data storage and processing

- personal data exchange with other third party systems (personal or institutional)

- integration of (personalized) public data

- exporting personal data for public (e.g. statistical) use

- exchange of private personal data messages

References:

Swan, M., 2012. Sensor Mania! The Internet of things, wearable computing, objective metrics, and the quantified self 2.0. J Sens Actuator Netw, 1, 217-253.

Johansen, M. A., & Henriksen, E., 2014. The evolution of personal health records and their role for self-management: A literature review. Stud Health Technol Inform, 205:458-462.

Samoocha, D., Bruinvels, D. J., Elbers, N. A., Anema, J. R., van der Beek, A. J., 2010. Effectiveness of web-based interventions on patient empowerment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res, 12(2).

Mosa, A. S. M., Yoo, I., Sheets, L., 2012. A systematic review of healthcare applications for smartphones. BMC Med Inform Decis Making, 12(1), 1-31.

Teng, X. F., Zhang, Y. T., Poon, C. C., Bonato, P., 2008. Wearable medical systems for p-health. IEEE Reviews in Biomedical Engineering, 1, 62-74.

Pantelopoulos, A., Bourbakis, N. G., 2010. A survey on wearable sensor-based systems for health monitoring and prognosis. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C: Applications and Reviews, 40(1), 1-12.

European Parliament, 24 Oct. 1995. Directive 95/46/EC. In Official Journal L 281, 0031-0050.

104th U.S. Congress, 21 Aug. 1996. Health insurance portability and accountability act. In Public Law 104-191.

European Commission, 2012. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Protection of Individuals with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data (General Data Protection Regulation), http://ec.europa.eu/justice/data-protection/document/review2012/com_2012_11_en.pdf.

Authors: George Drosatos (DUTH), Eleni Kaldoudi (DUTH)

Date: 26 November 2015